A new study from the Genomics and Microbial Evolution Group at the Miguel Hernández University of Elche (UMH), along with the Host-Microorganism Interactions Department at St. Jude Hospital (Memphis, USA), sheds light on one of the great mysteries of microbiology: why only some strains of common bacteria become pandemic agents. The work, published in the scientific journal ‘PNAS’, focuses on ‘Vibrio cholerae’, the bacteria responsible for cholera.

According to the academic institution in a statement, the study reveals that its «most dangerous» form arises thanks to a «specific combination» of genes and variants that give it an advantage in the human intestine. This research could open up new avenues for predicting and preventing future cholera epidemics.

The study is the result of a collaboration between UMH researcher Mario López Pérez and Professor Salvador Almagro-Moreno from St. Jude Hospital. Also involved are Professor José M. Haro Moreno and predoctoral student Alicia Campos López from the Department of Plant Production and Microbiology at UMH.

Through a comprehensive analysis of over 1,840 genomes of ‘Vibrio cholerae’, the team has identified that the species is divided into eleven distinct groups. The pandemic group belongs to the largest and is located within a lineage shared with environmental strains.

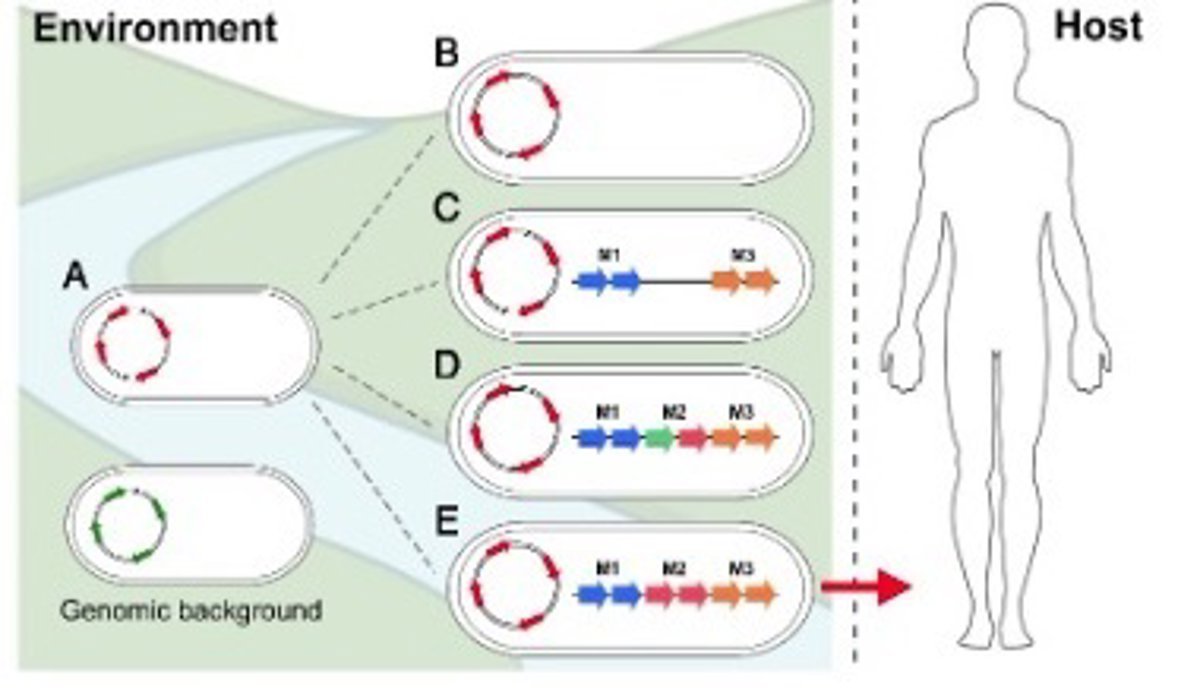

The findings suggest that pathogenic strains causing global cholera epidemics «emerge only when certain allelic variations are combined with the acquisition of unique modular gene groups that provide a competitive advantage during intestinal colonization.»

These characteristics act as a «critical bottleneck» that prevents the majority of environmental strains from becoming human pathogens. «The result is that only a small group of ‘Vibrio cholerae’ strains are capable of causing cholera in humans, despite the wide diversity of this species in nature,» explained UMH researcher Mario López, lead author of the study, who added that they are questioning «why only this small group has managed to cause pandemics.»

The research reveals that the emergence of cholera pandemic strains is limited by specific genetic bottlenecks. It requires: a genetic background with previous virulence adaptations, the acquisition of key genes such as CTXF or VPI-1, their organization into specific modules, and finally, certain unique allelic variants. «Only when all these elements coincide can a strain become a pathogenic clone with pandemic potential,» explained the professor.

These characteristics are not present in other environmental strains of ‘Vibrio cholerae’ and seem to have given pandemic strains a «key» competitive advantage: a greater ability to colonize the human intestine. «Interestingly, the genetic characteristics that allow cholera bacteria to infect humans are of no use to them for thriving in their natural environment,» López explained.

NATURAL HABITAT

The natural habitat of ‘Vibrio cholerae’ is aquatic environments, where it can be found freely or in colonies of cyanobacteria, mollusks, or crustaceans. As a disease, cholera is endemic in parts of the world with poor water, sanitation, and hygiene infrastructures. Outbreaks can also occur after natural disasters that affect these infrastructures.

The infection is characterized by severe, sudden, and high-volume episodes of watery diarrhea, leading to rapid dehydration and potential death if not immediately treated.

«Our analytical model could be applied to other environmental bacteria to understand how pathogenic clones emerge from populations that are not initially pathogenic,» highlighted the UMH expert. Additionally, the study opens the door to more accurately monitor which strains have pandemic potential, which could be useful for preventing future health crises.

The research has been supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through the CAREER program (#2045671) and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund through the Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease program (#1021977). It has also been funded by the Spanish project «Micro3gen» PID2023-150293NB-I00, co-financed with FEDER funds and managed by the Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness.